[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1B9cKDpa8Wo]

In the world of professional sports, the kinds of sports with championships and agents and assistant general managers studying statistical evidence, people pay a lot of attention to the correlation between age and peak performance. When there are millions of dollars on the line it is good to know what effectiveness might be expected for your dollar. And, outside of injuries, some typical patterns emerge.

For straight-up athleticism, the decline typically begins around age 26. While experience, wisdom, and a mature attitude towards training and health can extend the peak until perhaps age 30, barring the introduction of performance enhancing drugs, an athlete’s 30s are basically a battle to slow down the decline and stay viable. By the 40s you are just holding on, seeing how long you can even compete, much less dominate.

We skateboarders like to consider ourselves different – perhaps more artists than athletes. With a few ridiculed exceptions, professional skateboarders don’t “train” during the “offseason”, they don’t have “coaches”, they rarely are provided “healthcare”, they are often “intoxicated”, heck, most of them aren’t even getting paid a “living wage”. Yet, athletes they are and the peak performance pattern still holds up.

Pre-pubescent kids can show amazing talent but are yet to develop the strength and style of an adult body. The late teen / early 20s set are going crazy, touring for months straight, leaping down big sets straight out of the van, recovering quickly from injuries, smoking spliffs and drinking beers, literally while skating. But this is where many start to fall off. Some descents are caused by a decline in ability, some from injury, some just lose interest and explore the possibilities to get paid for more lucrative talents, but mostly, and sadly, so many great careers fall off from a decline of skateboard riding effort. Lifestyle casualties.

With the exception of Dustin Dollin, one typically needs to sober up (or at least get that shit under control) or already have accumulated enough brand-name popularity to get paid through the long tail of the late 30s and early 40s decline in productivity. Big street rails give way to waxed indoor park ledges. Impact gets substituted for smooth style, unique spots, and wise trick selection. Check out the blossoming fine-art career that is enough to keep that name on a board for a couple more seasons. They might not have a part in the new full length but they are performing an acoustic set during the premiere.

Knowing this pattern, one would think more skateboarders, or at least team managers, would do their best to squeeze out the greatest quantities of heavy tricks while the getting is good. To clock as much footage as possible before back pain, a spiraling chemical dependency, and/or the need to feed your family pushes you out of the spotlight.

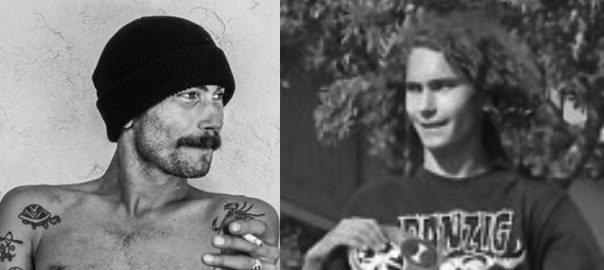

Dakota Servold gets it. After 6 or 7 years of being a workhorse pro for a board company that apparently doesn’t pay much, as well as riding the peaks and troughs of the clothing sponsor rollercoaster, Dakota left it all on the field for his new show sponsor, Emerica. Not that he phoned it in for the past three Foundation videos, but Green is something else.

As discussed in his Nine Club podcast interview and then again in his recent Thrasher Magazine interview, Dakota wised up, took his job seriously, and pushed his limitations. Longtime Servold friend, Emerica TM, and Green filmer Tim Cisilino concurs, “… we sort of just wanted to make it happen for each of us together. We both agreed that people who work hard get rewarded so we both were working our asses off to be the best we could be.”

And it shows. The backside 180 ender would be evidence enough, but you can pull nearly any trick from the part and behold something special. The endless front blunt rail. The ollie over the Chase sign. The man-ledge version of the ramp rail ollie to curb grind. The solid frontside 50-50 transfer to backside tailslide on the kinked rail. That improbable kick flip up the loading dock. These tricks hit hard and fast, but none feel like filler. And as a fan of both normal stance skating and non-pinched handrail grinds, I have no complaints.

What I like best about this narrative is the lack of a rock bottom. As far as I know, Dakota’s career wasn’t in jeopardy from his drinking and lack of productivity. He hadn’t wrecked a car or got dropped by key sponsors or blown out his knee and couldn’t skate or gotten hooked on heroin or anything that dire. He isn’t even claiming alcoholism or lifetime sobriety. He simply made a choice to give it his all. To look back on this well documented time with pride and not wonder how good he could have been ‘if only’… but to know… Very. Fucking. Good.

With all this concentration of peak performance, I was curious if Dakota had considered quitting smoking. Tim Cisilino: “Nah, he loves that too much.”

Big thanks to Tim for answering my rambling questions.